End of Year Update

December 2022 2022 has been a year of reemergence for APL. After two years where our markets and customer projects largely stopped due to the pandemic, we’re happy to see your projects starting again, and a similar return to near full activity across APL departments. We’re also simply pleased to still be here after a decade+—despite a few bumps and bruises—but moreso with vastly advanced machines vs a decade ago, and incredible memories of all the people we’ve met around the world, during this ongoing story of taming gasification for general use and global impact. All of us have been……

APL Powers the Verge Microgrid, Again

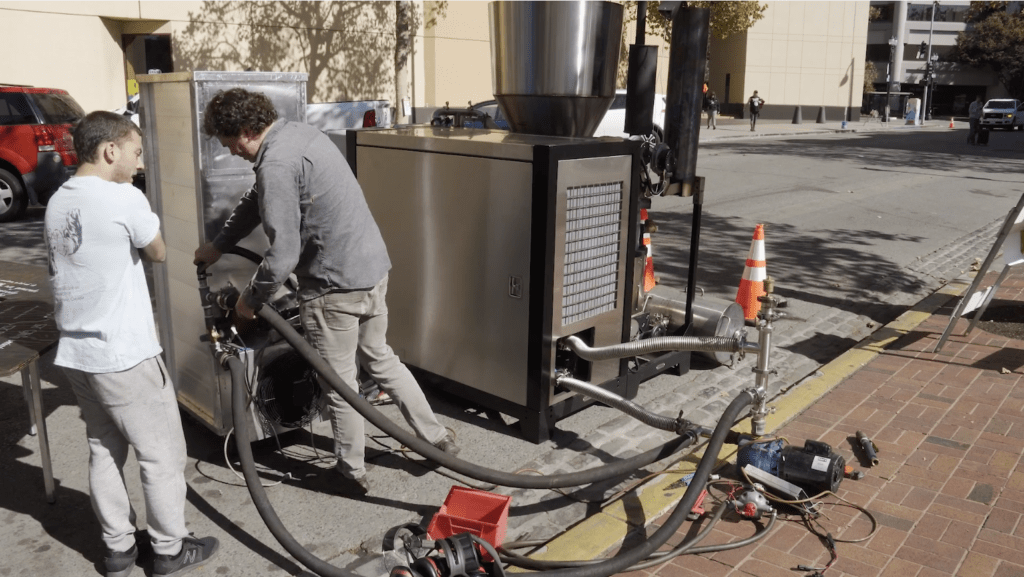

ALL Power Labs will be running our latest model Power Pallet, a PP30 v2.01 at The Verge Climate Tech Event being held at the San Jose Convention Center from October 25th – 27th. We’ll be set up outside at the Innovation Plaza on San Carlos St. and providing the base-load power for the microgrid that provides all the electricity used on the display floor by exhibitors as well as on the main stage. We make continuous improvements to our technology and this PP30 has numerous innovations adopted in this version 2.01. All PP30’s now include as standard equipment DeepSea DSE8610……

APL Summer Open House- Chartainer – 50 kW CHP Demo, Biochar available

After a long pandemic pause, we’re finally restarting our Open House / Open Shop for all interested to come see the works inside All Power Labs. These are always fun and informative events, with a great gathering of folks, and good food and drink for you too. So get out of the house and join us at our first open house in two years! The event is free, but RSVPs are needed. When: Friday September 30th, 2022, 5-7 PMWhere: APL Headquarters, 1010 Murray St, BerkeleyRSVP: Eventbrite Yes, the pandemic hit APL very hard–with markets stopping all around the world–but we were able……

APL Wins Another SBIR Grant

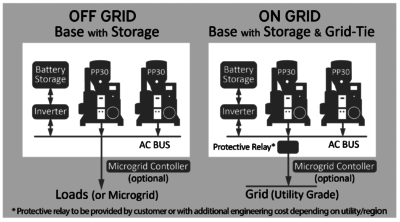

The U.S. Department of Energy has awarded All Power Labs (APL) a Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grant for their renewable energy submission in the amount of $200K to develop Distributed Energy Resources (DER). The SBIR program, also known as “America’s Seed Fund,” grants are distributed annually by the U.S. Department of Energy in various topic areas for small businesses. APL was previously an awardee of a National Science Foundation SBIR grant in 2016, which was used for the development of their Power Pallet systems. During Phase I of this SBIR grant APL will be developing support infrastructure for the……

Biochar and Bioenergy 2019, Fort Collins CO

APL team member Austin Liu at our Biochar & Bioenergy 2019 booth All Power Labs recently attended the Biochar & Bioenergy 2019 conference held in Fort Collins, Colorado from July 1–3. Our CEO, Jim Mason, as well as biochar experts Austin Liu and Aidin Massoumi were on hand, to promote our distributed-scale biomass gasifiers, share our work with SkyCarbon Biochar and the Local Carbon Network waste-to-climate products initiative, and soak up the latest knowledge from academics, producers and practitioners in the global biochar community. The event was hosted by the US Biochar Initiative (USBI) and featured presentations, panel discussions and……

Leave a Positive Trace: Permaculture Action Day with Burning Man

Photo credit: Brooke Porter Photography On Saturday, June 22, the Local Carbon Network joined Burners without Borders, the Permaculture Action Network, and nearly 400 participants for an all-day event at Hoover Elementary School in Oakland, CA, featuring live music, arts, food and hands-on projects to improve the school’s garden and outdoor classroom. The activity was part of the ‘Leave a Positive Trace’ action weekend organized by Permaculture Action Network in partnership with the community associated with the annual Burning Man arts and music festival. Hoover Elementary is located in a West Oakland neighborhood considered a ‘food desert’ due to the……

Summer Solstice Char-B-Que Open House at Gill Tract

On Friday, June 21, All Power Labs and the Local Carbon Network hosted an open house at UC Gill Tract Community Farm, our regenerative farming partner in Albany, CA. The Summer Solstice Char-B-Que Open House showcased the innovative integration of biochar co-composting into regenerative farming practices. More than 60 attendees were given tours of the two-acre organic farm and medicinal herb garden, and were shown the remarkable changes to soil and plant health that Gill Tract has observed since it started co-composting with SkyCarbon Biochar more than a year ago. To further celebrate the Northern Hemisphere’s longest day, we unveiled……

We won!

We’re honored to announce that All Power Labs is part of the winning team for the Water Abundance XPRIZE 2018. APL was the technical lead for the Skysource/Skywater Alliance team, and brought gasifier based power generation, plus a unique use of water vapor from biomass, to the larger problem of making atmospheric water generation machines truly usable in the world. The $1.5M award was announced at the XPRIZE Visioneering 2018 event in Los Angeles, October, 20, 2018, bringing to a conclusion a 2 year long competition involving 98 contending teams from 27 countries. The prize was launched in 2016 at……

Local Carbon Network: Terni, Umbria- Italy launch

Kickstarter Crowdfund in process. Join us for a 10 day learning holiday on a rural Italian farm,with Power Pallet, biochar, and composting (and all the other Italian provincial pleasures). This is the Valle Santa / Reiti Valley, where the APL New Farms Labs is located. We’ve been running machinery at this site for about four years now, and using it as the headquarters for APL efforts in Italy and the EU. With our transition to the Local Carbon Network model of deployment, we’re now recasting this site as our second major full circle “waste-to-valve, sky-to-soil” operating hub.Those following our Local Carbon Network project will know……

APL monthly Open House continues this Friday

We’ve restarted our monthly Open House events at All Power Labs. Now that we’ve launched the new PP30 Cogen-CS, and the Local Carbon Network is up and running, we have new reasons to gather the interested at our facility in Berkeley CA. This month we’re having the event this Friday, Sept 14th, from 5-7pm The Open House events are free. The food and drink are free. All you have to do is RSVP here. And bring your friends. PP30 Cogen-CS Demonstration [caption id="" align="alignnone" width="600"] The Open House is an opportunity to see APL machines in operation and discuss your potential……